China is back, and even the most ardent skeptics of Beijing’s policy easing will be compelled to admit that there is great upside in global oil demand in 2023. China has been allocating huge export and import quotas, nudging its oil refiners as hard as possible. Against the background of US economic readings rising quicker than expected and increasing the likelihood of a soft landing, as well as of Europe soon implementing its import ban on Russian products, there are several bullish factors that should push oil prices higher, in fact much higher than they are right now. Add to this the biggest position-taking spree into oil since November 2020, with investors swinging enthusiastically into net long positions (in Brent the long-short ratio is already up at almost 6:1), one would ask themselves why are we not seeing a much more pronounced market reaction. The Middle East, arguably the largest benefactor of oil volatility in 2022, has been wondering exactly that. With there being no real upside to global supply and plentiful upside to global demand, why do we keep on cutting prices for several consecutive months already?

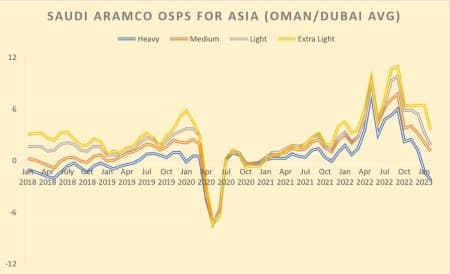

Chart 1. Saudi Aramco’s Official Selling Prices for Asian Cargoes (vs Oman/Dubai average).

Source: Saudi Aramco.

Saudi Aramco found itself between a rock and a hard place when setting the February 2023 official selling prices. On the one hand, ever since the Russian oil price cap kicked in, Saudi Arabia was believed to be the main go-to nation to alleviate Europe’s need to find new sources of supply. Combined with the prospect of a returning China, this should have normally translated into more demand for Saudi crude. On the other hand, the market dynamics were once again shifting to the disadvantage of Riyadh as the Middle East’s key oil marker, the Dubai futures contract, saw a steep decrease in December with the cash-to-futures spread falling by $1.60 per barrel month-on-month. As a consequence, Saudi Aramco cut its formula prices for the third consecutive month, with Arab Light down by $1.45 per barrel compared to January, falling to the lowest level since November 2021, a mere $1.80 per barrel to the Oman/Dubai benchmark.Related: U.S. Oil Rig Count Slips Again

Chart 2. Saudi Aramco’s Official Selling Prices for Northwest Europe-bound cargoes (vs ICE Brent).

Source: Saudi Aramco.

When pricing its grades into Asia, Aramco cut the lighter ones much more than the heavies, a trend that it also followed with its European prices where Arab Light was lowered by $1.40 per barrel, coming in at a -$1.50 per barrel discount to ICE Brent. In just six months since September 2022, the average formula price in Asia plummeted by $8 per barrel, whilst in Europe the decline was milder, only $5-6 per barrel. Just as Saudi Aramco finalized the merger of Aramco Trading and Motiva Trading, moving all of its trading activity under one umbrella, prices of US-bound cargoes continue to boggle the mind as the Saudi NOC rolled over the same prices for the fourth straight month. Hardly a surprise than exports to the United States are a mere quarter of what they were in early autumn, competing with late 2020 readings for the title of weakest flows on record with only three tankers departing towards the US this month.

Chart 3. ADNOC Official Selling Prices for January 2023 (set outright, here vs Oman/Dubai average).

Source: ADNOC.

The Emirati national oil company ADNOC and renewable energy are not the first association that comes to mind, however recently, with the naming of the NOC’s chief executive Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber as the president of the UN COP 28 conference, that has indeed been the case. In many ways, this year will be very eventful ADNOC. Earlier this month, the Emirati NOC established Adnoc Gas from its gas-focused assets in both processing and LNG and boosting gas reserves of 290 TCf intends to hold an IPO of a minority stake in the newly formed company. When it comes to ADNOC’s pricing of its grades into February 2023, the overall decline in oil prices nudged the exchange-traded price of Murban lower to $80.11 per barrel, more than $10 per barrel lower than the month before, with the light sour benchmark’s premium to Dubai shrinking again to $3 per barrel. As the medium sour complex appreciated, so did Upper Zakum, a grade that has seen some heavy discounting in recent months – its February differential to Murban was back at -$3.10 per barrel.

Chart 4. Iraqi Official Selling Prices for Asia-bound cargoes (vs Oman/Dubai).

Source: SOMO.

Slowly but surely, Iraq is consolidating its federal powers, greatly aided by increasing revenues from oil (which have risen to $115.5 billion last year, up approximately $40 billion compared to 2021). Exactly a year after last year’s Supreme Court decision that Kurdistan’s oil and gas laws are unconstitutional and contradict Iraq’s federal nature, the same court has now ruled that Baghdad’s federal budget transfers, too, are unconstitutional and should be brought to an immediate halt. After years of tacit coexistence between the federal powers in Baghdad and the Kurdish regional government in Erbil, the pressure on the latter is intensifying – most oil services companies have given up on Kurdistan so as not to lose out on bigger deals in southern Iraq, last year ExxonMobil relinquished its assets there and now trading major Trafigura is also severing its connections with KRG. The end game might take place anytime soon, with the state oil marketing company SOMO regaining marketing rights over Kirkuk crude.

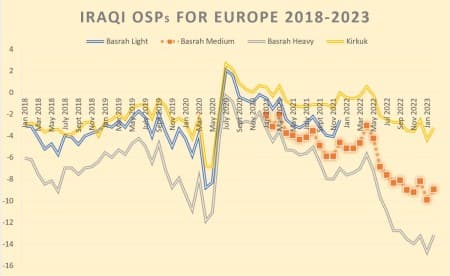

Chart 5. Iraqi Official Selling Prices for Europe-bound cargoes (vs Dated Brent).

Source: SOMO.

Whilst internal matters have been progressing relatively well for Iraq, the external pricing environment is forcing SOMO to walk the line and do what other Middle Eastern exporters are doing, too. At the same time, realizing that Iraq overdid some of the price bidding earlier in 2022, SOMO has cut February OSPs into Asia, however it did so by less than Saudi Aramco or KPC. Consequently, Basrah Medium and Basrah Heavy are both down by $0.90 per barrel compared to January, setting them at a -$1.40 and -$5.95 per barrel discount to the Oman/Dubai average, respectively. Iraqi pricing into Europe has arguably marked the one marked difference across all exporters as SOMO increased its prices by $0.95-1.60 per barrel, going the opposite way of Saudi Aramco that cut its formula prices by approximately $1 per barrel. Such a dramatic shift does not necessarily stem from an Iraqi perception of Basrah being underpriced, rather is a reflection in European pricing benchmarks. As SOMO bases its prices of Dated Brent which plunged to a sizable discount to ICE Brent (Saudi Aramco’s pricing basis) recently, this needed to be reflected in formula prices, too. Regardless of the initial trigger, it is a welcome development for Iraq as it will now garner more for its crude.

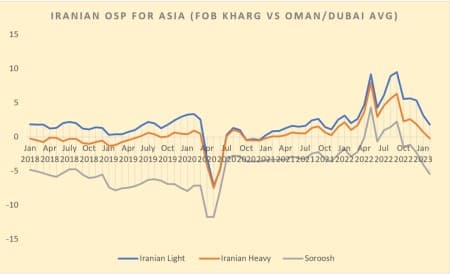

Chart 6. Iranian Official Selling Prices for Asia-bound cargoes (vs Oman/Dubai average).

Source: NIOC.

Iran traditionally took its time to publish its February prices, releasing them 20 days after Saudi Aramco, though it remains an open question whether they matter still considering almost all of the exports anyway go to China at a discount. Perhaps the idea behind NIOC’s was to wait out the trilateral sanctions of the US, EU and UK which agreed on a new round of restrictions placed on both individuals and organizations linked to the IRGC. At the same time, Tehran is getting increasingly confident in its ability to place cargoes as its 2023 budget is counting with exports of 1.4 million b/d at an average price of $85 per barrel. This is quite ambitious considering that, according to Kpler data, there has not been a single month last year when Iranian crude exports reached this level. Iran’s official selling prices for February 2023 reflect this confidence, with Iran Light into Asia lowered by $1.35 per barrel from the previous month, resulting in the same differential to Oman/Dubai as Arab Light ($1.80 per barrel), the first time this happened since December 2020.

Chart 7. Kuwait Export Blend Official Selling prices, compared with Arab Medium and Iran Heavy (vs Oman/Dubai average).

Source: KPC.

Whilst still generating solid profits from its oil exports, Kuwait is struggling to find its mojo when it comes to delivering promised outcomes on time. Its government resigned again in the second half of January, lasting only six months since the previous collapse, yet perhaps even more importantly, the progress that KPC managed to make with the 615,000 b/d al-Zour refinery, the largest downstream unit being commissioned currently, is minimal. Of the three distillation units only one is operational and the second would only start at some point in Q2, confirming that the delays will be even worse than though (the refinery was supposed to be running in 2020 already). On the other hand, Kuwait’s exports remain stable, churning out the same 1.9 million b/d as it did a year ago. Amidst all this, KPC continues to follow the trend set by Saudi Aramco and cut the price of its Kuwait Export crude by $1.05 per barrel from January’s $2.10 per barrel premium to Oman/Dubai.

Source: https://oilprice.com/