Pipelines are the unsung backbone of the global energy system–quietly moving billions of barrels of oil and trillions of cubic feet of gas with unmatched efficiency, reliability, and scale. In the U.S., they handle nearly 70% of all petroleum shipments, or over 14 billion barrels annually, without the headlines or volatility of seaborne trade.

What makes pipelines indispensable isn’t just cost or carbon footprint; it’s continuity. Cross-border systems like Russia’s Druzhba and Canada’s Keystone aren’t just conduits; they are arteries of energy security, designed to bypass naval chokepoints and harden supply resilience. These corridors knit together producers and consumers across continents, often out of sight, but never out of play.

Yet pipelines also create friction lines. Infrastructure that cuts across borders or bottlenecks (Strait of Hormuz, Suez Canal, Strait of Malacca) can become geopolitical flashpoints. Disruptions in these zones don’t stay local. They echo globally in the form of price spikes, inventory swings, and rebalanced trade flows.

Control over these assets is power. It brings not just throughput revenue, but strategic influence, something increasingly visible in cross-continental projects like the Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline, where infrastructure is both a commercial instrument and a geopolitical wager. As nations race to secure demand and derisk supply, pipeline politics is once again front and center.

Here are the 9 most geopolitically and economically significant oil and gas pipelines in the world:

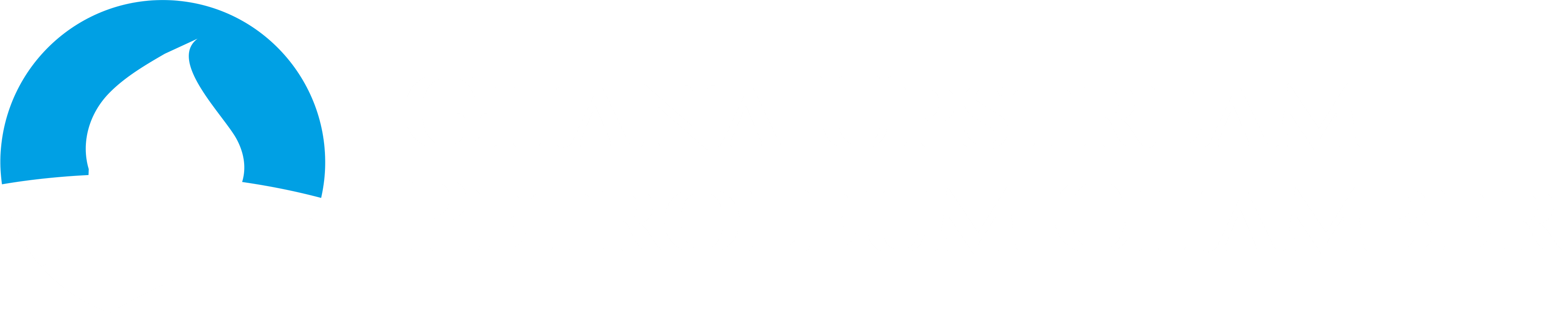

Druzhba Pipeline (Russia to Central Europe)

Crude oil: up to 1.2–1.4 million barrels/day

Ownership: Transneft (Russia)

The Druzhba Pipeline, also known as the “Friendship Pipeline”, remains one of the largest and most geopolitically sensitive crude transport corridors in the world. Completed in 1964 to link Soviet oil fields to Warsaw Pact markets, the system now stretches over 4,000 kilometers from Russia through Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, terminating in Germany.

With a peak capacity of approximately 1.4 million barrels per day, the network is supported by a series of mainline and intermediary pumping stations and tank farms totaling roughly 1.5 million cubic meters in crude storage.

Druzhba has outlived its Soviet political origins but not its strategic importance. It continues to anchor Russian crude flows into Central and Eastern Europe, even as war-related disruptions and EU diversification efforts steadily erode its reliability. Several branches have been repeatedly idled, rerouted, or mothballed due to physical sabotage, sanctions-related payment bottlenecks, and commercial realignment.

As of late June 2025, pipeline flows remain fractured. Reuters reported on June 26 that U.S. crude inventories had posted another unexpected drawdown, helping to lift Brent and WTI benchmarks, despite Druzhba-linked volumes to Germany falling sharply as Kazakhstan cut June deliveries to just 160,000 tonnes.

ESPO Pipeline (Russia to China and the Pacific)

Crude oil: ~1.0 million barrels/day to China

Ownership: Transneft and Rosneft

The ESPO (Eastern Siberia–Pacific Ocean) pipeline is a Russian crude oil pipeline system that transports oil from Eastern Siberia to the Asia-Pacific markets. It’s operated by the Russian pipeline company Transneft. The pipeline consists of two main sections: the first connects Taishet to Skovorodino, and the second connects Skovorodino to an oil export terminal at Kozmino Bay on the Pacific coast. The Skovorodino branch extends through Mohe to Daqing, China.

Construction of the pipeline commenced in April 2006, with the section between Taishet and Talakan launched in reverse to pump oil from the Alinsky deposit in 2008. The initial capacity of the pipeline was 600,000 barrels per day, which increased to 1,000,000 bpd in 2016 with plans to expand it further to 1,600,000 bpd by 2025.

Nord Stream 1 & 2 (Russia to Germany)

Natural gas: 110 bcm/year (combined), both pipelines now inactive

Ownership: Gazprom + European energy firms

Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 are offshore natural gas pipelines that run from Russia to Germany under the Baltic Sea. The two 1,224-kilometre pipelines offer the most direct connection between Russia’s vast gas reserves and Europe’s energy-hungry markets. The twin pipelines have a combined capacity to transport 55 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas per year. Located in Western Siberia on the Yamal Peninsula, the Bovanenkovo oil and gas condensate deposit supplies the bulk of the gas transported by the Nord Stream Pipelines. Bovanenkovo has estimated gas reserves of up to 4.9 trillion cubic meters.

Nord Stream 1 has been operational since 2011, while Nord Stream 2, though completed in 2021, never entered service. Both pipelines have been at the center of geopolitical debate regarding energy security and European dependence on Russian gas. In September 2022, explosions damaged three of the four pipelines, leading to significant gas leaks and raising questions about sabotage.

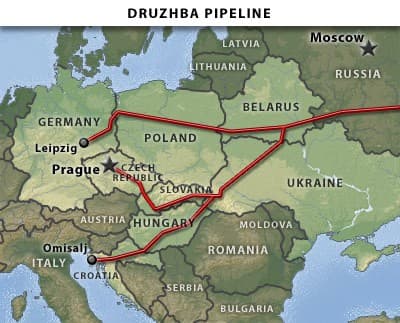

Keystone Pipeline System (Canada to U.S.)

Crude oil: ~590,000 barrels/day (existing system, excluding XL)

Ownership: TC Energy

The Keystone Pipeline System is a critical and politically charged component of North America’s crude oil logistics network. Now operated by South Bow, a company spun off from TC Energy’s liquids division, Keystone transports crude and bitumen from Alberta’s oil sands deep into the U.S. refining heartland. Its core segments connect Hardisty, Alberta, to Steele City, Nebraska, and onward to key refining hubs in Illinois, Oklahoma, and the Gulf Coast.

Phase I of the system stretches over 2,100 miles, delivering up to 590,000 barrels per day to Midwestern refineries. The broader network reaches as far as Port Arthur and Houston, Texas, integrating with the U.S. Gulf Coast’s export and processing infrastructure. The controversial Keystone XL expansion, once planned to add 830,000 bpd in capacity, was canceled in 2021 following sustained regulatory and political opposition.

Keystone has long stood at the intersection of energy strategy and environmental activism. Opponents argue that transporting diluted bitumen raises greater environmental and spill risks than conventional crude. Proponents counter that pipelines like Keystone enhance continental energy security, reduce reliance on seaborne imports, and support thousands of high-wage jobs in engineering, construction, and operations.

BTC Pipeline (Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan)

Crude oil: ~1.2 million barrels/day design capacity, ~600,000 actual

Ownership: BP-led consortium

The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline is a 1,768-kilometer-long pipeline spanning three countries that transports crude oil from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. It connects Baku, Azerbaijan, to Ceyhan, Turkey, passing through Tbilisi, Georgia. The pipeline became operational on May 25, 2005. The first phase of the pipeline was built by the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline company (BTC Co) and became operational in June 2006. The Azerbaijan and Georgia sections of the pipeline are operated by BP Plc. (NYSE:BP) on behalf of its shareholders in BTC Co., while BOTAS International Limited (BIL) operates the third section.

BTC originally had a throughput capacity of one million barrels per day, which BP has since expanded to 1.2 million barrels per day by using chemicals that reduce drag along the pipeline, thus allowing higher flow rates. Last year, 305 tankers lifted 29 million tonnes of crude oil from Ceyhan.

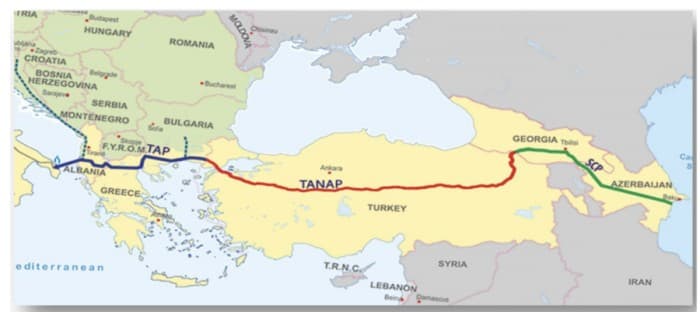

TANAP (Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline)

Natural gas: 16 bcm/year current, expandable to 31 bcm

Ownership: SOCAR, BOTA?, BP, SGC

Source: Azerbaijan Ministry of Energy

The Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) pipeline system is located in Turkey, stretching from the Turkey-Georgia border to the Turkey-Greece border, linking the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP) and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). The 1,811 km natural gas pipeline transports natural gas extracted in Azerbaijan to Turkey and then to Europe. The first phase of the pipeline was commissioned in June 2018, while the second phase of the pipeline was completed in November 2019. Back in 2020, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan christened TANAP a “regional peace project” before announcing that the pipeline had reached its maximum capacity of 32 billion cubic meters of gas annually.

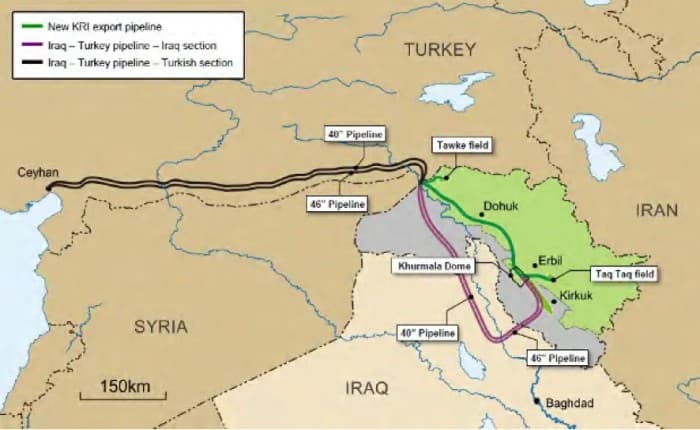

Iraq–Turkey Pipeline (ITP)

Crude oil: ~500,000–600,000 barrels/day when operational

Ownership: SOMO, Turkish Ministry of Energy

Kirkuk-Ceyhan Oil Pipeline, also known as the Iraq–Turkey Crude Pipeline (ITP), is an operating oil pipeline that runs from the City of Kirkuk in northern Iraq to the Mediterranean terminal of Ceyhan in Turkey. The first phase of the 986-kilometer pipeline was completed in 1976, while the second parallel pipeline was completed in 1987. The pipeline system has a total capacity of 1.4 million bpd, effectively making Iraq the largest supplier of oil to Turkey while also providing an alternate route for the Middle Eastern producer to export its oil.

Unfortunately, last year, Turkey suspended oil flows through the ITP after the ICC ordered the country to pay Iraq ~ $1.5 billion for past oil deliveries and to suspend export of crude oil from Kurdistan transported through ITP. The pivotal pipeline has now remained closed for two years.

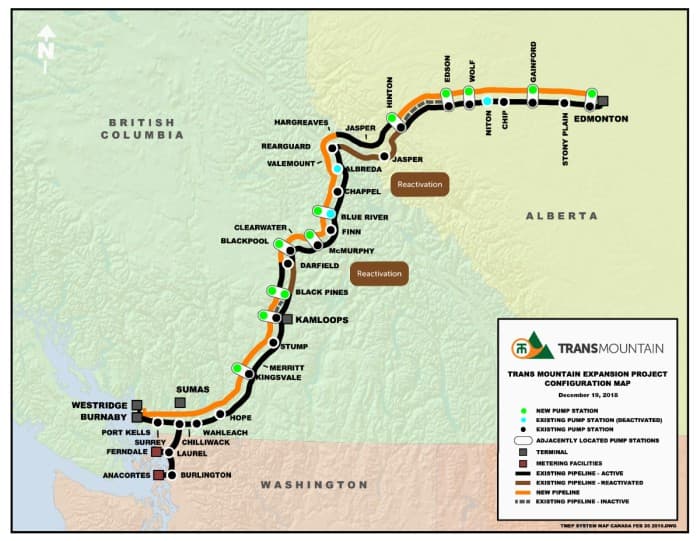

Trans Mountain Pipeline (Canada)

Crude oil and products: expanded to ~890,000 barrels/day (from 300,000)

Ownership: Government of Canada

The Trans Mountain Pipeline is a Canadian pipeline system that carries crude and refined petroleum products from Edmonton, Alberta, to the coast of British Columbia, with delivery points in Kamloops, Sumas, and Burnaby. The Trans Mountain Expansion Project (TMX), which doubled the pipeline’s capacity, became fully operational in May 2024.

The expansion of TMX was intended to lower the Canadian oil industry’s reliance on US-bound pipelines and American refiners, which forced Canadian producers to accept deeper discounts for their crude as well as leaving them exposed to oil price shocks. However, TMX is facing fresh challenges. While the project has successfully opened new export markets for Canadian crude oil, particularly to Asia, some companies are hesitant to pay the higher tolls associated with the project’s cost overruns. This has resulted in utilization rates below initial forecasts, though the pipeline continues to provide significant economic benefits to Canada.

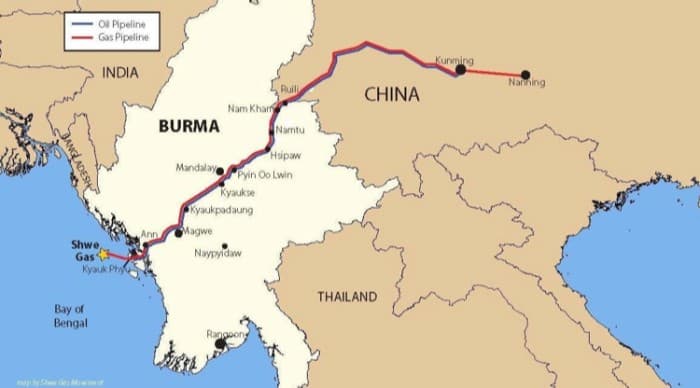

China-Myanmar Oil and Gas Pipelines

Crude oil: ~440,000 barrels/day

Gas: ~12 bcm/year

Ownership: CNPC

The China-Myanmar Oil and Gas Pipelines are a strategic bypass best considered as China’s engineered response to the so-called Malacca Dilemma. Stretching roughly 800 kilometers through Myanmar, the dual pipeline corridors allow Beijing to sidestep one of Asia’s most vulnerable maritime chokepoints. Crude oil sourced from the Middle East and Africa is offloaded at Myanmar’s Kyaukphyu port and piped directly into Yunnan Province, while a parallel gas line channels offshore natural gas to both China and domestic Myanmar markets.

This inland route offers Beijing a rare overland alternative to the heavily patrolled Strait of Malacca, through which over 80% of China’s oil imports have traditionally passed. More than just a hedge against naval disruption, the pipelines support four offtake stations within Myanmar, supplying local energy needs and reinforcing bilateral interdependence. For Myanmar’s government, the project has also become a vital revenue stream, anchored by steady transit fees and infrastructure payments from China.

The corridor illustrates the broader logic of China’s Belt and Road energy playbook: diversify routes, secure inland access, and extend regional leverage through fixed infrastructure. In an era of exposed sea lanes and shifting alliances, few links are as subtly significant.

Source: By Alex Kimani for Oilprice.com